At the Intersection of Science and Art

December 8, 2022

It should not come as a surprise to anyone that art and science are siblings. Faced with a lump of clay, a potter has a world of infinite possibility at their beck and call. Every revolution of the potter’s wheel is the beginning of a journey, of an experiment. With much trial and error, with experimentation and experience, artists and scientists alike inevitably come to the same place: discovery, spurred by curiosity.

Watch the video above to see Brett in action or read on for a taste of what lies in store above.

Art Driven by Process

Brett Crawford is the head of the Musculoskeletal Therapeutic Area for BioMarin Research. Brett the scientist has been working to find treatments for genetic diseases at BioMarin since 2013. Brett joined BioMarin when we acquired Zacharon Pharmaceuticals in 2013 for its SensiPro platform – which Brett developed. With 41 publications under his belt and a deep understanding of glycobiology, Brett is a key leader among our scientists.

Brett the artist has been making ceramics since 1990. Brett the scientist applies scientific principles – theory, experimentation, failure, or success – to his work and his art. Brett the artist brings curiosity and imagination to his pottery which bleeds over into his work.

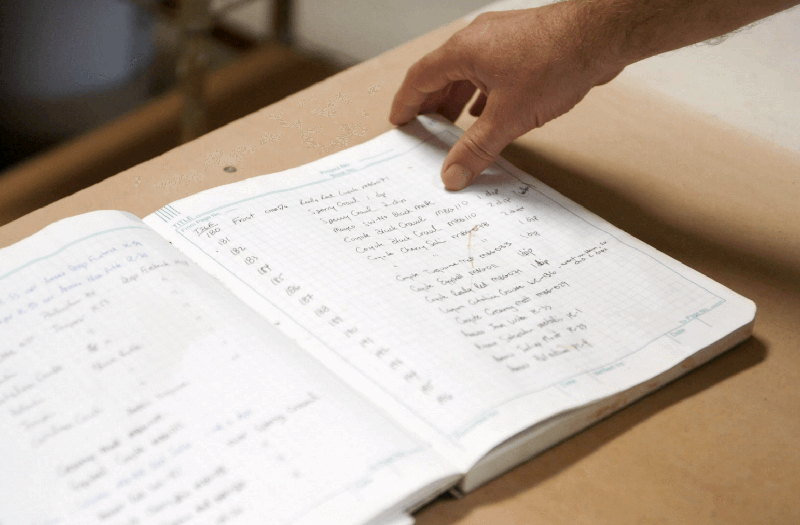

Figure 2 In this lab journal, Brett tracks the combinations of clay and glaze used in his experiments

“In science we spend years in school learning the basics of biology and the mechanisms of human disease and come out with this foundation of knowledge,” Brett says. “How do you put all those pieces you learned together to develop a treatment for a rare genetic disease? It’s an exciting creative process.”

Showing us more of his pottery, Brett continues to talk about his methods, and it’s easy to see the scientific influence at work in his ceramic approach. “I have a standard operating procedure. You learn the foundations of working with clay and then the fun and creativity is tweaking them and breaking them,” he explains. “Every once in a while, some new technique works really well, so I’ll spend the next two or three years exploring that and digging deeper into it.” Brett tracks his artistic failures and successes in a journal, much as he does his lab work, with orderly notation throughout. “Wedging the clay, preparing it for the wheel, centering it, opening it, lifting it, shaping it, every step requires the one before it being done right,” Brett explains. “This is where science and art synergize.”

Walking Among Giants

If there is a Venn diagram for artists and scientists, the point of overlap would be large.

Galileo Galilei, for example, is sometimes referred to as an astronomer, but his illustrations of the canyons of the moon, or spots on the sun, made it possible for anyone to see the cosmos. Leonardo da Vinci is often thought of as an artist thanks to the Mona Lisa, but his architectural musings have proven sound. Over 400 years after the design for a bridge Da Vinci was commissioned to create was rejected, the Vebjørn Sand da Vinci Project used the designs to build a bridge in Norway. Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph and the Morse code, started life at Yale aspiring to be an artist of history paintings.

Figure 3: Brett in the lab among peers

This combination is undoubtedly powerful. With the artistic side exploring new possibilities, and the scientific side methodically inquiring and discovering, ultimately it is the patients who are in the best position to benefit from this duo of mindsets.